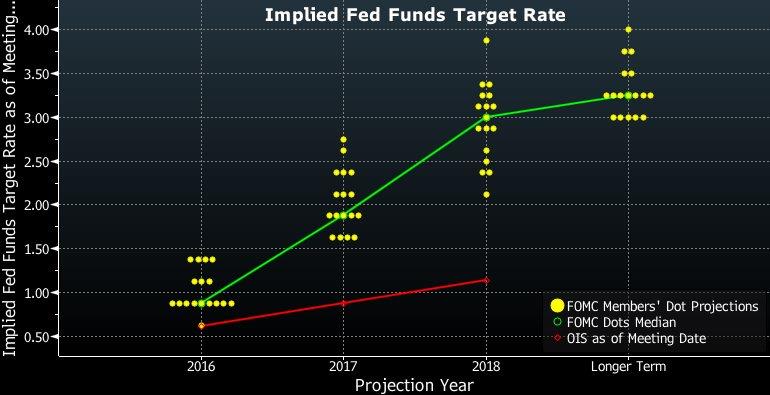

The Short Term In March Australian sovereign debt delivered a 0.9% loss and was one of the worst performers among global debt markets. The 10-year government bond yield rose from 2.39% to a high of 2.70% and currently sits at 2.50%. As a result, Australia offers one of the highest 10-year yields among sovereigns that have a top grade credit rating from all three rating agencies including the US where Australia offers a premium of 67 basis points. This follows the worldwide debt rally that kicked off 2016 when poor performing equity and commodity markets forced investors into a flight to quality. However, this is now beginning to settle and many are regaining confidence in these asset classes. Global equity markets have risen by 5.5% over the last month while oil has climbed almost 50% off its low point. Over the last 2 weeks, futures traders’ expectations for the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) to cut the cash rate by 25 basis points has declined from 12% to 7% prompting markets to believe that Governor Glenn Stevens will end his tenor with inaction for his final 10 months at the helm. However, this has been inconsistent with the rest of the world which has seen a very busy start to the year in terms of monetary policy. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand recently cut rates, the Bank of Japan entered negative territory and expectations for the number Federal Reserve rate hikes for 2016 have declined from 4 to 2 (increments of 25 basis points).  Source: Bloomberg This activity has had a knock-on effect to Australian sovereign debt as global inflation expectations have shifted from prolonged deflation to moderate low inflation over the long term. Another factor driving further yield widening can be attributed to the Fed. Historically, the long end of the Australian Government bond yield curve has been strongly correlated to the US. With two potential US rate hikes in the coming years we should see this part of the curve steepen. Essentially, longer term sovereign bonds are largely a function of inflationary expectations. With the US and China making up almost two thirds of global GDP, these types of credit securities are relatively sensitive to economic policy decisions as these economies are a gauge on long term global economic growth and stability. In our view, the expected tightening of the Fed later this year has not yet been correctly priced in to Australian sovereign debt and as a result, investors can expect further widening for the rest of 2016 The Long Term Taking a longer term view, Australia’s credit rating may be at risk. With Treasury forecasts indicating federal budgets deficits to continue into the next decade, Australia’s public debt could trigger a sovereign rating downgrade. Eleven economies currently hold the triple-A credit rating but post-GFC the budgetary repair of Australia has been slower than other developed countries. This would be detrimental to both government bonds and domestic credit markets. Sovereign bonds would reflect a higher risk premium while major banks would be charged higher interest rates for overseas borrowing. As a result, banks would have to raise their interest rates which would dampen Australian economic growth. Effectively, the cost of funding would increase throughout Australia negatively feeding through to domestic credit markets. Although this is a long way off, it is still a possibility and investors should be aware of the downside if this trend continues.

Source: Bloomberg This activity has had a knock-on effect to Australian sovereign debt as global inflation expectations have shifted from prolonged deflation to moderate low inflation over the long term. Another factor driving further yield widening can be attributed to the Fed. Historically, the long end of the Australian Government bond yield curve has been strongly correlated to the US. With two potential US rate hikes in the coming years we should see this part of the curve steepen. Essentially, longer term sovereign bonds are largely a function of inflationary expectations. With the US and China making up almost two thirds of global GDP, these types of credit securities are relatively sensitive to economic policy decisions as these economies are a gauge on long term global economic growth and stability. In our view, the expected tightening of the Fed later this year has not yet been correctly priced in to Australian sovereign debt and as a result, investors can expect further widening for the rest of 2016 The Long Term Taking a longer term view, Australia’s credit rating may be at risk. With Treasury forecasts indicating federal budgets deficits to continue into the next decade, Australia’s public debt could trigger a sovereign rating downgrade. Eleven economies currently hold the triple-A credit rating but post-GFC the budgetary repair of Australia has been slower than other developed countries. This would be detrimental to both government bonds and domestic credit markets. Sovereign bonds would reflect a higher risk premium while major banks would be charged higher interest rates for overseas borrowing. As a result, banks would have to raise their interest rates which would dampen Australian economic growth. Effectively, the cost of funding would increase throughout Australia negatively feeding through to domestic credit markets. Although this is a long way off, it is still a possibility and investors should be aware of the downside if this trend continues.