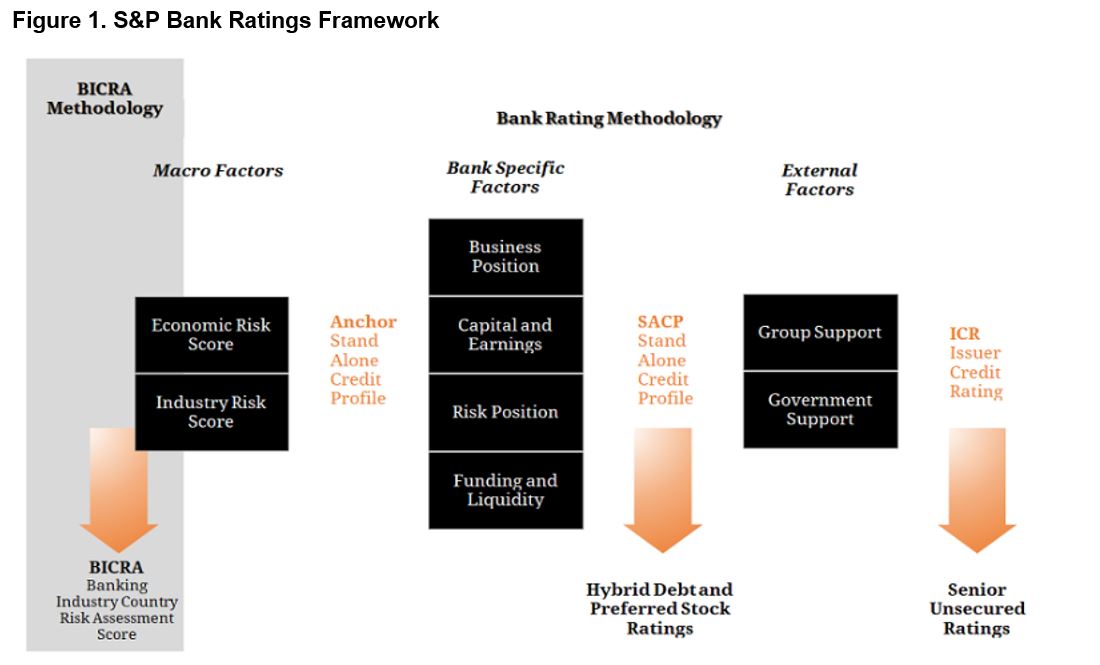

Credit rating agencies such as Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s (S&P) have been in focus throughout 2018 as investors have watched the Australian financial landscape increasingly enter new territory. This has largely been a function of the Royal Commission into Banking and Financial Services, as well as the more unstable political environment seen throughout the year. However, despite the negative press that has dominated the headlines throughout the year, credit ratings for the major banks and Australia have, quite rightly, been largely unaffected, and to some extent, have even seen some positive moves in the last 12 months. On 20 September 2018, S&P revised its outlook on Australia’s sovereign debt rating from AAA / Negative to AAA / Stable. Some of the major factors behind this decision include the budget’s return to surplus, a robust housing market, expected government revenue growth coupled with expenditure restraint, a strong labour market and reasonable commodity prices. This represented a reversal from two years ago, when we wrote an article explaining S&P’s Bank Credit Rating Framework following the agency’s decision to place Australia’s ‘AAA’ rating on CreditWatch Negative, citing negative fiscal budgetary pressures. Whilst the return to a ‘Stable’ outlook is unlikely to influence the agency’s outlook on the major banks (which remain unchanged at ‘Negative’), it does potentially have positive credit implications for these institutions, particularly bank hybrid instruments. Broadly, the S&P Rating Methodology for Banks consists of two key steps:

- Determining the Stand-Alone Credit Profile (SACP) of the issuer and;

- Establishing the likelihood of extraordinary support to determine the bank’s Issuer Credit Rating (ICR).

Figure 1 below provides a quick overview of the mechanics behind S&P’s rating assessment methodology. Figure 1. S&P Bank Ratings Framework  Source: BondAdviser, S&P The last time S&P altered the credit ratings of Australian authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) was when it downgraded 23 banks (both domestic and foreign branches) in May 2017. Notably, this downgrade was a direct result of Australia’s Banking Industry Country Risk Assessment (BICRA) being downgraded from ‘2’ to ‘3’, as the Economic Risk score fell from ‘3’ to ‘4’. The higher economic risk score (which implies increased economic risk) translated into higher risk-weights for the banks’ assets (loans) in the calculation of S&P’s projected risk-adjusted capital ratio (RAC). Earlier in October 2018, S&P released the results of its survey of the world’s 100 banks and noted that Australia’s Big Four banks’ RAC ratios had fallen sharply relative to domestic peers to sit between 40th and 50th in the world. The Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) said that S&P’s May 2017 downgrade reduced the RAC ratios of the Australian banks by ~90 basis points but it is important to note that based on APRA’s domestic capitalisation requirements, the Big Four banks remain on-track to meet the 2020 “unquestionably strong” levels ahead of time (figure 2). Figure 2. Australian Bank Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) Ratios

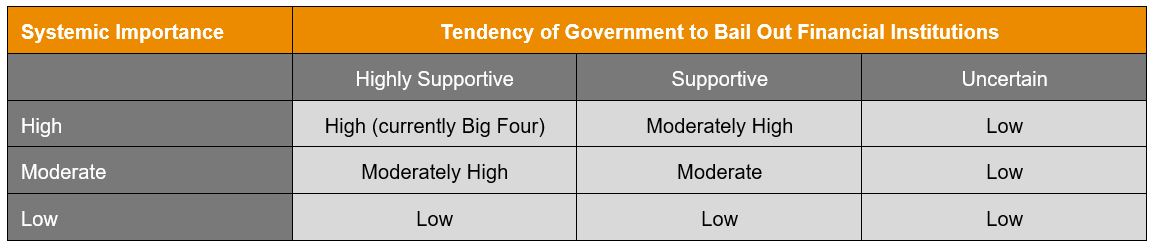

Source: BondAdviser, S&P The last time S&P altered the credit ratings of Australian authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) was when it downgraded 23 banks (both domestic and foreign branches) in May 2017. Notably, this downgrade was a direct result of Australia’s Banking Industry Country Risk Assessment (BICRA) being downgraded from ‘2’ to ‘3’, as the Economic Risk score fell from ‘3’ to ‘4’. The higher economic risk score (which implies increased economic risk) translated into higher risk-weights for the banks’ assets (loans) in the calculation of S&P’s projected risk-adjusted capital ratio (RAC). Earlier in October 2018, S&P released the results of its survey of the world’s 100 banks and noted that Australia’s Big Four banks’ RAC ratios had fallen sharply relative to domestic peers to sit between 40th and 50th in the world. The Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) said that S&P’s May 2017 downgrade reduced the RAC ratios of the Australian banks by ~90 basis points but it is important to note that based on APRA’s domestic capitalisation requirements, the Big Four banks remain on-track to meet the 2020 “unquestionably strong” levels ahead of time (figure 2). Figure 2. Australian Bank Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) Ratios  Source: BondAdviser, Company Reports Relative to the SACP, the rating for senior unsecured and hybrid debt works on a notching basis (up for senior debt and down for Tier 2 and Tier 1 capital instruments). Senior debt is given an uplift if the agency believes these companies are “too big to fail” (i.e. major banks) and hence, in a stressed scenario the government will step in and provide support. On the other hand, they do not expect governments to step in for capital instruments if there is a bank failure (i.e. a point of non-viability is reached), which is the reason why these securities are notched down. In a financial crisis, a government will often (but not always) provide additional support if it believes damage to the economy outweighs the overall cost to taxpayers. Currently, the four major banks enjoy a 3-notch (the highest) uplift in the ICR stemming from government support (figure 3). However, one other important consideration for domestic bank ratings is Australia’s looming response to the resolution and Total Loss-Absorbing Capacity (TLAC) reforms being implemented by financial regulators around the world. TLAC aims to define a total amount of a firm’s capital structure that could be converted to equity in distressed situations, reducing the need for the government safety net currently afforded to the banks. Figure 3. Likelihood of Government Support for the Banks

Source: BondAdviser, Company Reports Relative to the SACP, the rating for senior unsecured and hybrid debt works on a notching basis (up for senior debt and down for Tier 2 and Tier 1 capital instruments). Senior debt is given an uplift if the agency believes these companies are “too big to fail” (i.e. major banks) and hence, in a stressed scenario the government will step in and provide support. On the other hand, they do not expect governments to step in for capital instruments if there is a bank failure (i.e. a point of non-viability is reached), which is the reason why these securities are notched down. In a financial crisis, a government will often (but not always) provide additional support if it believes damage to the economy outweighs the overall cost to taxpayers. Currently, the four major banks enjoy a 3-notch (the highest) uplift in the ICR stemming from government support (figure 3). However, one other important consideration for domestic bank ratings is Australia’s looming response to the resolution and Total Loss-Absorbing Capacity (TLAC) reforms being implemented by financial regulators around the world. TLAC aims to define a total amount of a firm’s capital structure that could be converted to equity in distressed situations, reducing the need for the government safety net currently afforded to the banks. Figure 3. Likelihood of Government Support for the Banks  Source: BondAdviser, S&P Should APRA follow in the footsteps of other global regulators and introduce equivalent measures here, it would inevitably lead to additional costs to the major banks to refinance existing instruments with TLAC-compliant debt securities. With an initial proposal expected ‘by the end of the year’, investors should be aware of all potential implications for senior unsecured debt from this mechanism. Hybrid holders conversely, may actually benefit if S&P’s BICRA changes from 2017 are reversed and we may even see a double notch contraction in rating differentials over the next few years. We would lastly note that this morning (8 November 2018), APRA released a discussion paper on Increasing the loss-absorbing capacity of ADIs to support orderly resolution which, of about five options, appears to favour an expansion of the Tier 2 market as its preferred approach. We will outline our thoughts on this separately and made an editorial decision to publish this article mostly in its existing format.

Source: BondAdviser, S&P Should APRA follow in the footsteps of other global regulators and introduce equivalent measures here, it would inevitably lead to additional costs to the major banks to refinance existing instruments with TLAC-compliant debt securities. With an initial proposal expected ‘by the end of the year’, investors should be aware of all potential implications for senior unsecured debt from this mechanism. Hybrid holders conversely, may actually benefit if S&P’s BICRA changes from 2017 are reversed and we may even see a double notch contraction in rating differentials over the next few years. We would lastly note that this morning (8 November 2018), APRA released a discussion paper on Increasing the loss-absorbing capacity of ADIs to support orderly resolution which, of about five options, appears to favour an expansion of the Tier 2 market as its preferred approach. We will outline our thoughts on this separately and made an editorial decision to publish this article mostly in its existing format.