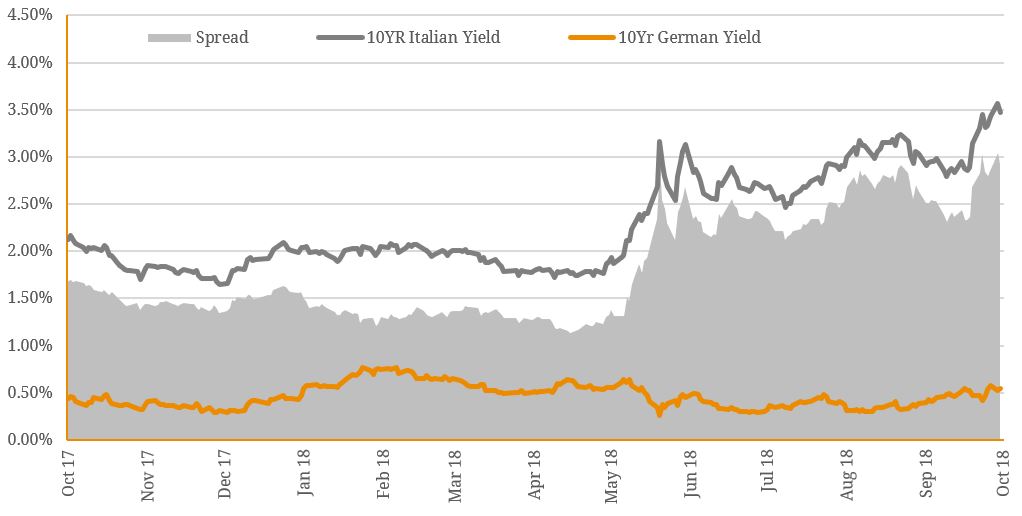

Earlier last week and before the more systemic selloff in risk assets, Italy’s 10-year government bond yields rose to a quite staggering 3.63% – the highest mark since 2014. Meanwhile, yields on the 10-year German Bund declined to an equally staggering 0.53% as the ‘lo spread’ between the two countries, which has long observed as a proxy for country risk, spiked 45 bps with the spread widening to 308 bps (figure 1) – a level not seen since the European debt crisis. The sharp rise in recent months can be partially attributed to the political turmoil that has engulfed the country, as the recently elected populist coalition attempts to defy the European Central Bank’s common rules with the regimes’ budget proposal in order to boost spending on universal income, tax cuts and to increase the country’s budget deficit to 2.4% despite boasting the largest debt deficit in the EU of €2.3 trillion. Figure 1. 10-Year Treasury Yields and the ‘Lo Spread’  Source: BondAdviser, Bloomberg Whilst a rogue political regime can influence yields to climb higher as investors demand an increasing risk premium for political uncertainty, it is unusual for a proposed budget deficit to push yields for a single country towards levels not seen since a continent-wide debt crisis in early 2010’s (10-year yields on Italian debt rose to over 7% in 2012). Recent spikes have also drawn attention to the serious flaws in Italy’s financial system, exposing the underlying risks present to both rating agencies and investors alike. These risks have been brought upon by some financial mismanagement post-GFC, with the country’s financial institutions stocking their balance sheets with high levels of government debt (figure 2). This has primarily occurred through the deployment of funding injections by the ECB rather than using this stimulus to boost lending in the economy, as intended. This misstep by Italian banks has potentially dire consequences for the country’s financial system and economy, as they stare down the all-to-familiar barrel of what has been coined, the ‘Doom Loop’ – where a troubled country’s banks increasingly hold their own sovereign debt. Figure 2. Italian Bank Holdings of Sovereign Debt (Total) & as a Percentage of Total Assets

Source: BondAdviser, Bloomberg Whilst a rogue political regime can influence yields to climb higher as investors demand an increasing risk premium for political uncertainty, it is unusual for a proposed budget deficit to push yields for a single country towards levels not seen since a continent-wide debt crisis in early 2010’s (10-year yields on Italian debt rose to over 7% in 2012). Recent spikes have also drawn attention to the serious flaws in Italy’s financial system, exposing the underlying risks present to both rating agencies and investors alike. These risks have been brought upon by some financial mismanagement post-GFC, with the country’s financial institutions stocking their balance sheets with high levels of government debt (figure 2). This has primarily occurred through the deployment of funding injections by the ECB rather than using this stimulus to boost lending in the economy, as intended. This misstep by Italian banks has potentially dire consequences for the country’s financial system and economy, as they stare down the all-to-familiar barrel of what has been coined, the ‘Doom Loop’ – where a troubled country’s banks increasingly hold their own sovereign debt. Figure 2. Italian Bank Holdings of Sovereign Debt (Total) & as a Percentage of Total Assets  Whilst the Doom Loop is not unfamiliar to a sovereign which experienced similar conditions in 2011, it is perhaps of more concern to a banking sector which holds ~84% more state debt in 2018 than it did when the last Doom Loop occurred, despite the governments best efforts to encourage banks to reduce their net debt exposure in 2017. Currently, Italian banks hold just under 20% of Italy’s issued sovereign debt, which is currently subject to constant mark-to-market losses, causing the banks overall assets to lose value and which also is eroding their Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio capital buffers (Figure 3). A sovereign yield increase of 200 bps is estimated to reduce CET1 ratios by approximately 67 bps, thus increasing the banking systems susceptibility to a financial shock and reinforcing the Doom Loop. Furthermore, higher sovereign bond holdings increase the risk of cross-contagion between the government and the financial sector in the euro region, which has historically had a strong interdependence between financials and sovereigns.

Whilst the Doom Loop is not unfamiliar to a sovereign which experienced similar conditions in 2011, it is perhaps of more concern to a banking sector which holds ~84% more state debt in 2018 than it did when the last Doom Loop occurred, despite the governments best efforts to encourage banks to reduce their net debt exposure in 2017. Currently, Italian banks hold just under 20% of Italy’s issued sovereign debt, which is currently subject to constant mark-to-market losses, causing the banks overall assets to lose value and which also is eroding their Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio capital buffers (Figure 3). A sovereign yield increase of 200 bps is estimated to reduce CET1 ratios by approximately 67 bps, thus increasing the banking systems susceptibility to a financial shock and reinforcing the Doom Loop. Furthermore, higher sovereign bond holdings increase the risk of cross-contagion between the government and the financial sector in the euro region, which has historically had a strong interdependence between financials and sovereigns.  Source: BondAdviser, Company Reports In what already appears to be a rather grim outlook for the country, one must then consider pending rating agency actions, expected later this month (Moody’s has already acted revising Italy’s sovereign outlook to ‘Negative’) and how these will likely add to the situation. Additionally, there are escalating tensions with the European commission, the risk of snap elections in February and concerns over public debt sustainability. Indeed, it appears that dark storm clouds are gathering over Italy’s banking system with significant headwinds impeding any future hope of economic growth. The current ‘financial storm’ Italy is facing should serve as another clear reminder to Australian regulators of the importance of maintaining ‘unquestionably strong’ banking capital buffers but also of the vital link to a strong sovereign rating.

Source: BondAdviser, Company Reports In what already appears to be a rather grim outlook for the country, one must then consider pending rating agency actions, expected later this month (Moody’s has already acted revising Italy’s sovereign outlook to ‘Negative’) and how these will likely add to the situation. Additionally, there are escalating tensions with the European commission, the risk of snap elections in February and concerns over public debt sustainability. Indeed, it appears that dark storm clouds are gathering over Italy’s banking system with significant headwinds impeding any future hope of economic growth. The current ‘financial storm’ Italy is facing should serve as another clear reminder to Australian regulators of the importance of maintaining ‘unquestionably strong’ banking capital buffers but also of the vital link to a strong sovereign rating.